‘Those things which occur to me, occur to me not from the root up but rather only from somewhere in the middle. Let someone then attempt to seize them, let someone attempt to seize a blade of grass and hold fast to it when it begins to grow only from the middle.’ Why is this so difficult? The question is directly one of perceptual semiotics. It’s not easy to see things in the middle, rather than looking down on them from above or up at them from below, or from left to right or right to left: try it, you’ll see that everything changes. It’s not easy to see the grass in things and in words.

—Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari

—Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari

Hideout @ Table of Contents

Hideout @ Table of Contents Portland, Oregon

Jan 24th — 29th, 2016

Artists

Exhibition Design

Exhibition Design

Jacob Gevalt, Paul Savovici, Shohei Takasaki

Joseph Magliaro

Joseph Magliaro

Audio

Maxx Bass, Alex Asher Daniel

Four walls, an elevated ceiling, parquet or concrete floors, movable dividers, and above all, an abundance of white. As the archetypal gallery design, the White Cube has come to consume the exhibition space. Growing concomitant with modernism, the White Cube represents a stripping down, the attempt to shed all external context and allow only the eternal, autonomous values of art to shine through. Even the viewer becomes an intruder in this pristine sanctuary of art. The artist and writer Brian O’Doherty, in his seminal series of essays, “Inside the White Cube,” describes this ideology as culminating not in the gallery space, but rather in the installation shot. “Here at last, the spectator, oneself is eliminated,” allowing for an uncontaminated, though necessarily distant and removed, experience of art and viewing.

It’s not that the White Cube is without its merits—is the frenetic bricolage of the salon really preferable?—but needless to say, it can feel a little stuffy. During the 1990s, a new type of work began to appear that the curator and critic Nicolas Bourriaud called relational aesthetics. Relational aesthetics does away with the love of the pure so intrinsic to the White Cube and instead views the work of art as a social interstice, bringing the outside in, and taking the everyday context as its focus. Soup, dancing, and even just hanging out: these materials, so prominent in works of relational aesthetics, also describe Hideout. No one aspect overshadows another—for Hideout the photo is just as important as the pho. Not quite a gallery, and not quite a party or event, Hideout is somewhere in between, combining contexts and turning ambiguities into possibilities. Hideout at Table of Contents takes place as a weeklong exhibition of shifting forms and events, between Sunday, January 24 and Friday, January 29. Bookended by the opening of a group exhibition featuring work by Jacob Gevalt, Paul Savovici, and Shohei Takasaki, and a closing party with DJs Maxx Bass and Alex Asher Daniel, the in-between is in flux, continuously in the process of becoming something else. The show passes through forms and configurations, as the fixtures are reworked and the environment reimagined, and hosts a variety of events, including workshops, screenings, and installations. There’s no static form; meaning is on the move.

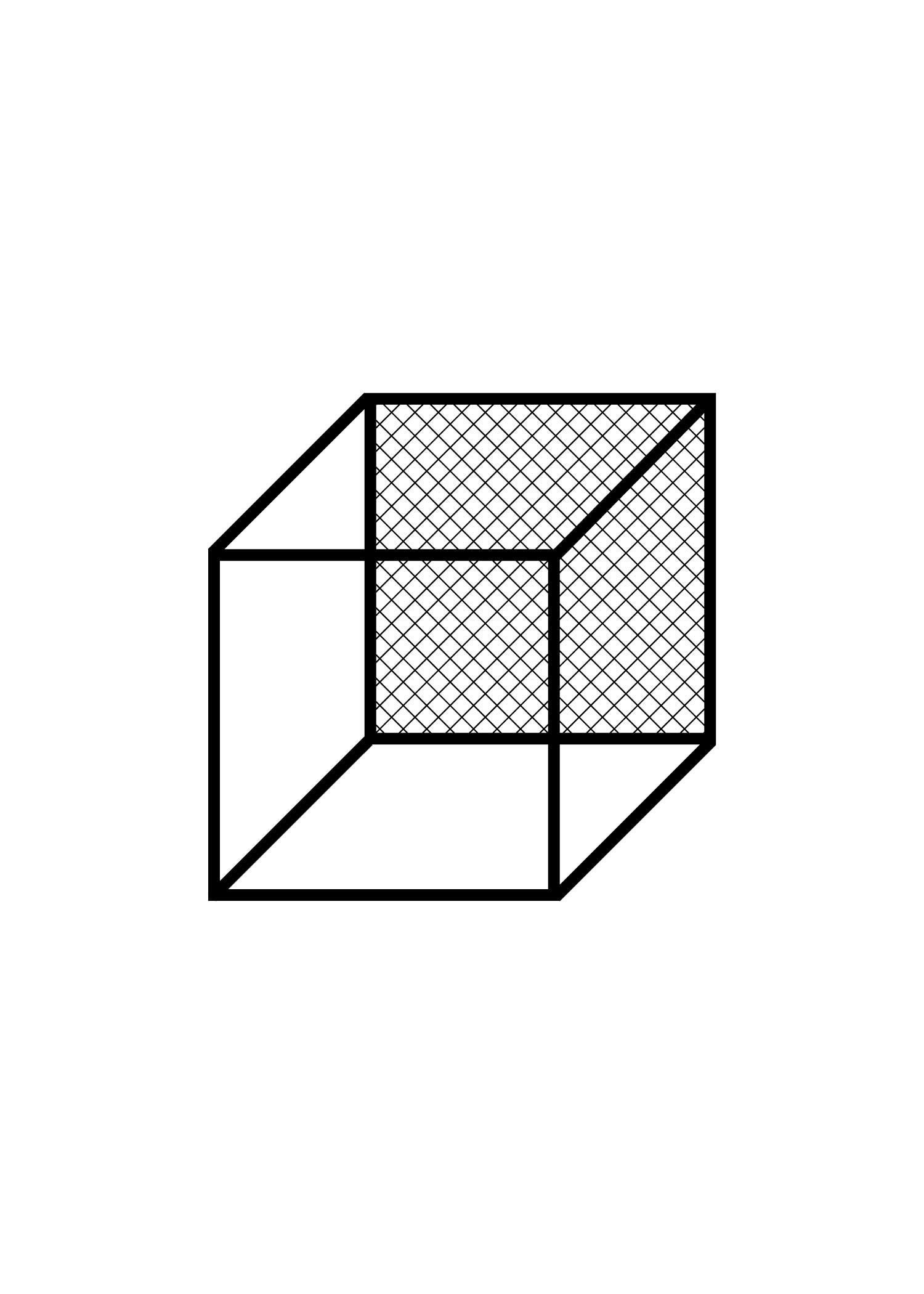

If the contemporary gallery is a White Cube, Table of Contents might be more like the Necker Cube. An assemblage that exceeds the sum of its parts, the Necker Cube transforms twelve lines, into a coherent, though unstable, visual system. As the viewer changes perspective, the shape and orientation of the cube shifts as well. It’s never possible to give a final description for the cube, it’s always somewhere in between, in the midst of a shift. When speaking of Table of Contents, there is a reluctance to describe it simply as a store. It has always been, at the same time, something else: a studio, a gallery, an environment. Though the Chinatown storefront is closing, there’s no end in sight. Both Table of Contents and Hideout act like grass. As described by philosopher Gilles Deleuze, “not only does grass grow in the middle of things but it grows itself through the middle... Grass has its line of flight and does not take root.” Table of Contents existed long before its fixed address as an itinerant experience and ethos, the storefront was simply something in the middle, a stop along the way. Hideout too, never promised something stable. It appears, briefly, before fading into the night. Above all, disappearance promises the possibility of return. Though at first glance it might seem like an end, take another look. We’re only in the middle.

It’s not that the White Cube is without its merits—is the frenetic bricolage of the salon really preferable?—but needless to say, it can feel a little stuffy. During the 1990s, a new type of work began to appear that the curator and critic Nicolas Bourriaud called relational aesthetics. Relational aesthetics does away with the love of the pure so intrinsic to the White Cube and instead views the work of art as a social interstice, bringing the outside in, and taking the everyday context as its focus. Soup, dancing, and even just hanging out: these materials, so prominent in works of relational aesthetics, also describe Hideout. No one aspect overshadows another—for Hideout the photo is just as important as the pho. Not quite a gallery, and not quite a party or event, Hideout is somewhere in between, combining contexts and turning ambiguities into possibilities. Hideout at Table of Contents takes place as a weeklong exhibition of shifting forms and events, between Sunday, January 24 and Friday, January 29. Bookended by the opening of a group exhibition featuring work by Jacob Gevalt, Paul Savovici, and Shohei Takasaki, and a closing party with DJs Maxx Bass and Alex Asher Daniel, the in-between is in flux, continuously in the process of becoming something else. The show passes through forms and configurations, as the fixtures are reworked and the environment reimagined, and hosts a variety of events, including workshops, screenings, and installations. There’s no static form; meaning is on the move.

If the contemporary gallery is a White Cube, Table of Contents might be more like the Necker Cube. An assemblage that exceeds the sum of its parts, the Necker Cube transforms twelve lines, into a coherent, though unstable, visual system. As the viewer changes perspective, the shape and orientation of the cube shifts as well. It’s never possible to give a final description for the cube, it’s always somewhere in between, in the midst of a shift. When speaking of Table of Contents, there is a reluctance to describe it simply as a store. It has always been, at the same time, something else: a studio, a gallery, an environment. Though the Chinatown storefront is closing, there’s no end in sight. Both Table of Contents and Hideout act like grass. As described by philosopher Gilles Deleuze, “not only does grass grow in the middle of things but it grows itself through the middle... Grass has its line of flight and does not take root.” Table of Contents existed long before its fixed address as an itinerant experience and ethos, the storefront was simply something in the middle, a stop along the way. Hideout too, never promised something stable. It appears, briefly, before fading into the night. Above all, disappearance promises the possibility of return. Though at first glance it might seem like an end, take another look. We’re only in the middle.

The other way of beginning again, on the other hand, is to take up the interrupted line, to join a segment to the broken line, to make it pass between two rocks in a narrow gorge, or over the top of the void, where it had stopped. It is never the beginning or the end which are interesting; the beginning and end are points. What is interesting is the middle.

—Gilles Deleuze

—Gilles Deleuze

Press

Highsnobiety, NBC KGW, Purple Diary

© 2013 - 2023 Galerie Hideout. All Rights Reserved.